Motivation

What Motivates People?

In the past few years we have seen a shift from a mass market model: everyone gets the same thing to a highly individualized model: I can get just what I want - as individuals we decide what we want to watch, read, listen to, and when without the restrictions of media company schedules or brick-and-mortar stores. In our workplace, we move more frequently from job to job, not because of the salary but because we want something more fulfilling, something more aligned with our values and our lifestyle. According to analysis by Guy Berger, Chief Economist at LinkedIn, people entering the workforce today will change positions twice as often within the first 5 years as compared to 30 years ago. Scientists call this phenomenon "the Copernican Turn": Where in the past organizations had set the rules for engagement, now individuals are more empowered as the center of their personal and professional lives, pulling experiences to them based on their individual needs and desires. For today's organizations, it means that we need new approaches to motivation and engagement, in order to attract and retain talent and maximize productivity and wellness (Self-Determination Theory in Human Resource Development).

We've been talking about human motivation since the 1950's and there has been a lot of research published on the topic. Despite all that knowledge, and despite the hundreds of millions of dollars invested annually in employee engagement, only a third of employees feel engaged in their work (Harter, 2016). So what are we doing wrong?

It is important that we understand what drives an individual before we try to apply any sort of motivational program like gamification. The business world is becoming accustomed to talking about extrinsic and intrinsic motivation and the realization that for intellectual work we should move away from extrinsic motivation and towards intrinsic motivation.

The research and evidence is overwhelming, yet very few companies understand and embrace the reality of what motivates people.

Frederic Herzberg's Two Factor Theory

Herzberg's research, documented in one of Harvard Business Review's most re-published articles One More Time: How Do You Motivate Employees identified two factors in motivating employees: hygiene factors and motivation factors. Hygiene factors can be a major distracter if they are not sufficiently looked after. Motivation factors come into play only if the hygiene factors are adequate; they form the basis for the motivation factors. All of the motivation factors are intrinsic.

- Five top hygiene factors (in order of importance):

- Company policy and administration

- Supervision

- Relationship with supervisor

- Work conditions

- Salary

- Five top motivators (in order of importance):

- Achievement

- Recognition

- Work itself

- Responsibility

- Advancement

Herzberg's research also showed how ineffective rewards and punishment are in motivating people. In describing this he coined the term KITA (kick in the ass) management model to describe this flawed approach to motivation. His paper is highly recommended for anyone involved in implementing Intelligent Swarming.

Daniel Pink's "Drive"

Daniel Pink is a New York Times columnist and author whose work we reference often. Daniel picks a topic, researches it in depth, and then writes highly accessible and widely praised books on the selected topic. His book Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us reviews numerous studies done on motivation. Drive compliments Herzberg's research and adds the critical factor of distinguishing physical tasks from cognitive or intellectual tasks. The traditional rewards and punishment, carrot and stick, KITA models work for physical tasks. Those same models fail miserably when the task requires thinking and judgment. Knowledge work is, by definition, intellectual work and yet time and time again we see organizations using the old motivation models from the world of physical work. This is in part because so many of our management practices have their roots in manufacturing. While organizations have evolved from creating products (or outcomes that are tangible) to creating value, memories, experiences, and services, the management practices have not evolved and are still based on the mentality of production lines and people doing physical work. The tiered support model with a level one, two, and three is an antiquated linear, production line approach applied to a different type of work. This intellectual work requires a different approach and a different model of engagement and motivation.

Key points from Drive:

- Motivation factors for physical tasks or work is different from the motivation factors for cognitive tasks

- The primary motivating factors for intellectual work are:

- Mastery - we like to get good at things

- Autonomy - we like to have control and choice over our activities and situation

- Purpose - alignment to and belief in a compelling purpose or value proposition, we are motivated when we care.

Deci and Ryan's Self-Determination Theory

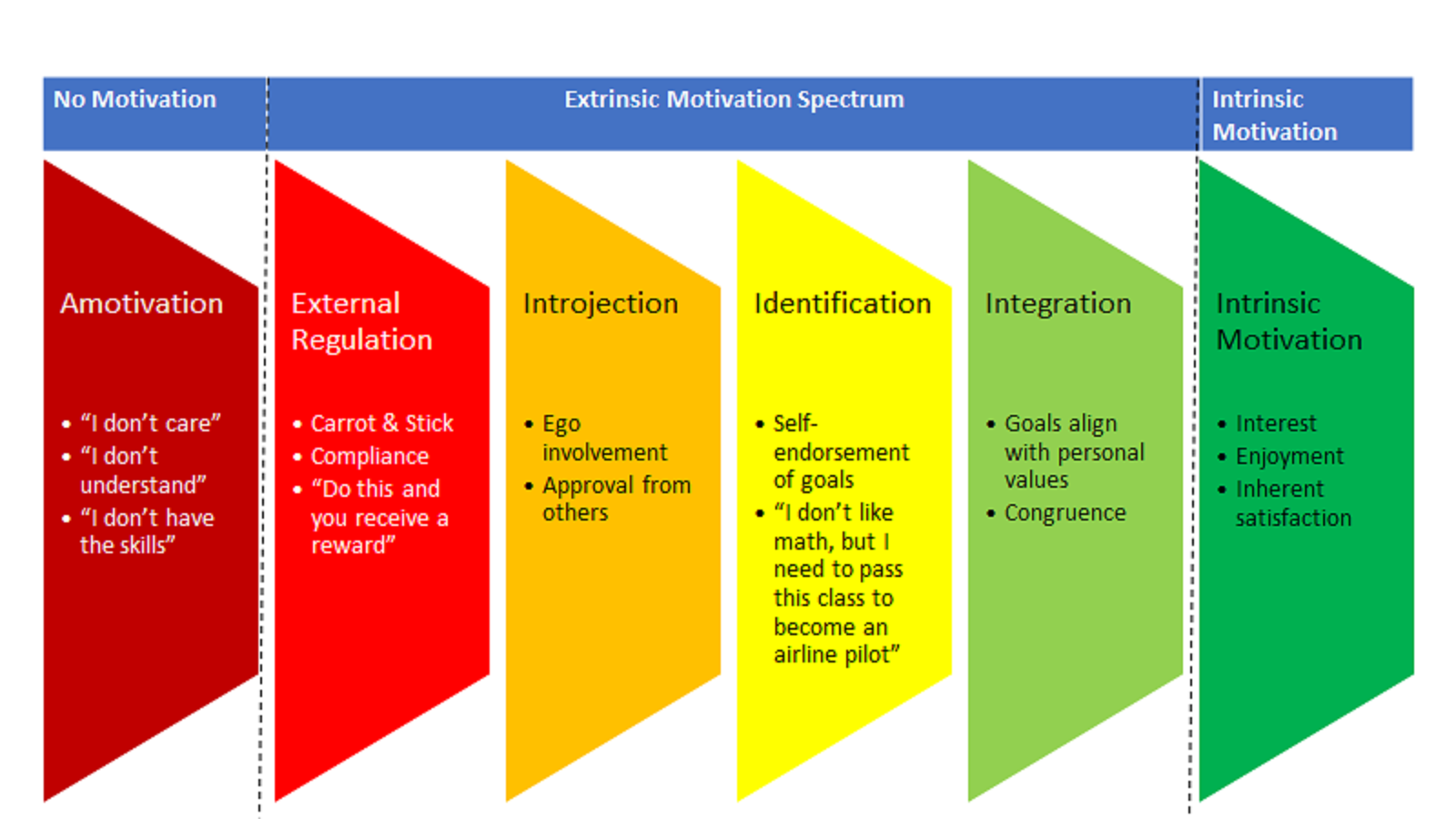

In Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness (by Richard Ryan and Edward Deci), we recognize that extrinsic motivation is not one single entity, but a spectrum: see image: The Motivational Spectrum.

The more an individual moves to the right of the spectrum, the more internally motivated they are.

The Motivational Spectrum Explained

Let's step through the Motivational Spectrum from left (Amotivation) to right (Intrinsic Motivation).

People who are not motivated (Amotivation) may require training to increase their skills, or coaching to understand the value of their role in the bigger picture. Or they are not in the right place. Reasons for amotivation can be diverse, as are their solutions. Once we are able to move people out of amotivation, they will end up somewhere on the extrinsic motivation scale.

External regulation is an entirely external driver, meaning that without the stimulus of rewards and punishment, the individual is not motivated to do a good job. This is what the business world traditionally thought of as the only type of extrinsic motivation. External regulation indeed works well for people who are doing physical, repetitive tasks (masons, for instance, are sometimes paid by the amount of bricks they lay). But the science shows that when we try to put these same mechanics in place for jobs that require the individual to use their brain more than their hands, external regulation doesn't work. Instead we would see individuals trying to "game the system" in order to receive the rewards as quickly as possible, or to avoid punishment. Here we find the cherry-pickers. Externally regulated individuals have no other goal than to receive the reward or avoid punishment.

Introjection is mostly an external driver, but also somewhat internal. An individual who is motivated through introjection is, above anything, seeking approval from other people. They want to be "employee of the month" with their picture on the wall. It's the specialist who hoards knowledge so that others always need to come to them for help. As long as the individual feels validated, they will be self-driven to improve their performance in order to increase validation. But if they are ignored or they feel under appreciated, their motivation to perform plummets.

Identification is more of an internal driver, but can require some external reinforcement: the individual understands that they need to improve their performance, because they require the outcome in order to achieve a personal goal. We see this for instance in highly technical support organizations, where someone is doing a great job not because they enjoy doing support, but because they want to get promoted to developer or technical consultant as quickly as possible. Or nurses, who need to train and re-certify regularly to maintain their position. The training itself might not be inherently satisfying, but it must be done in order to continue doing the work they love.

Integration is entirely an internal driver and as close to Intrinsic Motivation as you can get. But we must be careful not to confuse it with intrinsic motivation, because the trigger for the integration driver is still very much external. individuals whose motivation is through integration may not enjoy the tasks they perform, but they perform well because the outcome aligns with their personal goals, beliefs and values. Their personal objectives are, in a sense, the same as the objectives of the organization they work for.

When someone is intrinsically motivated, they do the task because they enjoy doing it. Hobbies are by definition activities where people are intrinsically motivated to do them.

Motivation in a Collaborative Environment

Now that we understand what motivates people around intellectual or cognitive work, we are in a position to help those who are not engaged. Intelligent Swarming requires that we design our workplace in a way that enables people to feel a sense of autonomy and mastery. Knowing what motivates knowledge workers offers opportunities to help improve performance.

Leadership's challenge is to create an environment in which people care: where the hygiene factors are taken care of and where people feel connected to the purpose and values of the organization. This is what enables people to feel good about their contribution and accomplishments: this is what motivates people to contribute. As we mentioned earlier, apathy is death to a collaborative environment. Apathy is a symptom of weak leadership.

The Power of "Opt-in"

A fundamental premise of Intelligent Swarming is the idea that people will choose to help: they will opt-in. We can see from the extensive research on motivation that autonomy or a sense of control and choice is a powerful motivator. As organizations consider adopting Intelligent Swarming, management is often quick to ask... "what if no one opts-in?" There are three factors at play here.

- The most powerful motivator is understanding and leveraging the motivation factors we have covered in this section.

- We have to ensure our measures and recognition systems are focused on value creation and not volume. We will get what we measure.

- We need to design and implement exception triggers; we need to detect and manage issues that are at risk of missing service level commitments. But, if we pay attention to the motivation factors and our measures, the frequency of exceptions will be minimal.

Successful adoption of the Intelligent Swarming model requires an understanding of what really motivates knowledge workers. Sticks and carrots, rewards and punishments, stack ranking, and leaderboards are not effective ways to motivate people to collaborate.